ROLE

- User Research + Interviewing

- Persona Creation

- Journey Mapping

- Rapid Ideation

- Usability Testing

- UI

DURATION

- 2-Week Sprint

TEAM

- Two

TOOLS

- Pen + Paper

- Adobe Illustrator

- proto.io

- Google Forms + MTurk

- Excel

DELIVERABLES

- Clickable Prototype (High-Fidelity)

Role

- User Research + Interviewing

- Persona Creation

- Journey Mapping

- Rapid Ideation

- Usability Testing

- UI

Team

- Two

Duration

- 2-Week Sprint

Tools

- Pen + Paper

- Adobe Illustrator

- proto.io

- Google Forms + MTurk

- Excel

Deliverables

- Clickable Prototype (High-Fidelity)

Brief:

For a student project, we were tasked with creating a concept design in response to the following prompt:

“The Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) wants to reverse the decline of ridership by finding a way to address the issue of crime and/or safety.”

Our Solution:

A mobile app that implemented the following features:

- Mobile call button options for reporting crime, and particularly harassment, on CTA

- A system for riders to track and share their rides with others

Research

What Efforts Has the CTA Made to Solve This Problem?

The city of Chicago recently invested in a 6-year, $8 billion initiative to “improve the commuting experience” of CTA riders, including:

- Continued “investment in technology” (e.g., CCTVs)

- Increased public education (e.g., anti-harassment campaigns)

- “Enhanced communications” with riders

Ethnographic Observations + User Interviews

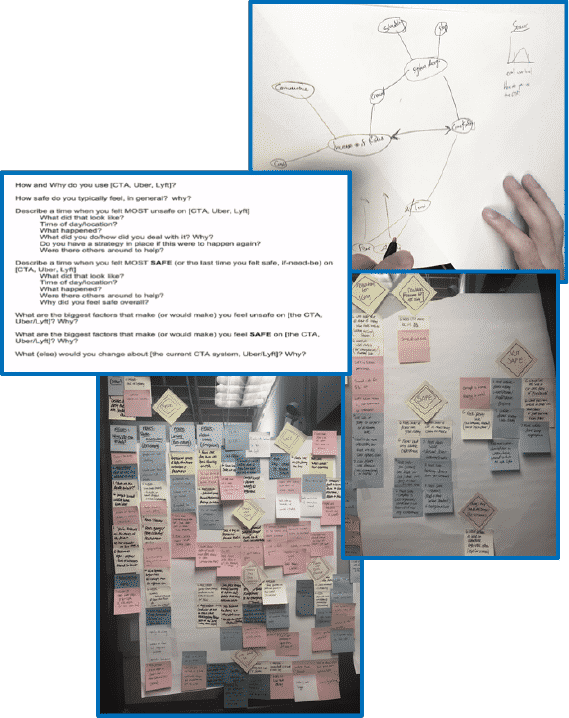

After collecting as much information as possible from the CTA, city press releases, and the media, we drafted up a topic map, which we used to formulate a (quick and dirty) set of questions. Although my partner and I both ride the CTA fairly regularly, we decided it was important to start off by observing common behaviors, issues, and potential pain points, framed under the context of safety. We spent the majority of a day observing (and riding) a few popular bus and “L” train stops/lines in the Chicago loop. We were also able to complete 6 guerrilla-style interviews (~5 min each) as a quick gauge of riders’ feelings and experiences in-transit. Since we anticipated riders to be in a hurry to catch their buses/trains, we crafted our questions to be very brief, and included a set of deeper follow-up questions in case any of our in-field interviewees had extra time (which, as we learned, they did not). The information we collected proved to be extremely helpful, however, and gave us more of a sense of direction to create a discussion guide for the 9 in-depth interviews we later conducted (30–40 min each; interviewees were screened by having any experience riding the CTA and were normally distributed by frequency of ridership).

Surveys

As the nation’s second-largest public transit system, CTA ridership encompasses a very large and diverse population. Because of this, we wanted to make sure we were collecting data from as representative of a sample as possible. We recruited as large of a sample as we could, given our time and budgetary constraints (n=50; same screening criteria as above). This helped further inform our decisions — and personally gave me some peace of mind that we weren’t just basing our designs exclusively off of those who were willing to chat with us (i.e., it potentially helped correct for some selection biases).

User Persona – Mayra

Mayra, 27, F

(One of Our Interviewees)

- Commutes on the L everyday, sometimes later at night

- Notices stations + trains are typically less populated at nighttime

→ Makes her feel vulnerable/at greater risk for being confronted or harassed

- During her commute, she is most comforted by seeing CTA staff and security presence because she knows she could reach to them for help if-need-be.

- She is somewhat comforted knowing there are emergency call buttons inside the train cars, but she isn’t sure what situations they’re intended for, who they contact, or if they even work.

- If she ever felt threatened or harassed on transit, Mayra would most likely not press the call button because she would not want to draw attention to herself, and is afraid pressing the button may do something drastic (e.g., stop the train or call the police).

- She would also feel uneasy not knowing what to do until help arrives (is she obligated to stay because she called?).

- She does, however, want to feel empowered to know what her options are, and who she could contact for help.

- In the case that Mayra feels particularly unsafe riding the L, she’ll resort to using a ridesharing service (such as Uber or Lyft), which can be significantly more expensive, but makes her feel much safer.

Synthesis

Why Wasn’t the CTA’s Initiative Working?

Observations from our in-depth interviews suggested that most riders (such as Mayra) would opt for a ridesharing service (e.g., Uber, Lyft) as a transportation alternative when they felt unsafe taking the CTA. What I found to be interesting about these services is that, although riders are essentially alone in a stranger’s car, they felt significantly safer and more in-control because they could (a) see where they were going in real-time (and even share with others), (b) see their driver’s rating beforehand, and (c) easily report any issues directly to the company.

These features became our main impetus for our competitive analysis, and we used them as criteria to evaluate the following apps (which addressed 2 main questions):

Competitive Analysis Pt. 1: How Have Other Cities Addressed This Issue?

Both Minneapolis and the BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) supplemented their Metro Transit apps with a “Text for Safety” feature, enabling riders to seek help if they don’t feel safe making a call; however, depending on the circumstances, user may not have enough time or attention to send a descriptive text message. Users also must indicate their location using a dropdown menu, which fails to leverage the phone’s GPS features and adds an extra step in the user flow. St. Louis recently partnered with SafeTrek to offer an app that pings police with riders’ location if their finger releases an emergency button, but users must memorize a random PIN and enter it once they’re safe, which many have reported is difficult and unintuitive to use.

Takeaway: When designing for situations in which users’ cognitive abilities may be compromised due to panic, it’s vital that the steps to reach help are simple, streamlined, and free of complicated features/options.

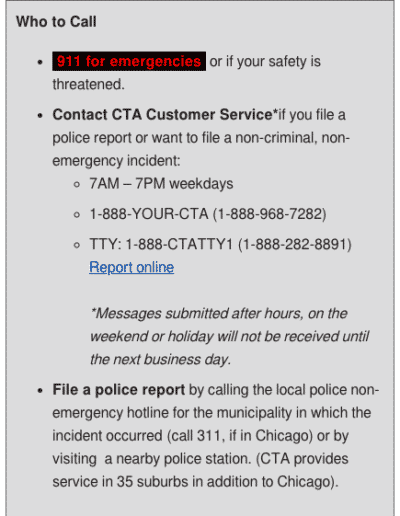

Competitive Analysis Pt. 2: What Options are Currently Available for Chicagoans?

Although there are no particular transit safety apps available for CTA riders currently, there are many CTA (as well as general transit) apps available for riders- we looked deeper into 3 of the most popular ones- Google Maps, Transit, and TransitStop (CTA-specific)

- Though these apps excel at real-time planning and tracking, Transit is the only one that displays specific train and car number information, which may be necessary to know (for the user and authorities) in certain emergencies or circumstances.

- Of all 3, Google Maps was the only option that enables the user to share their location with others.

We also looked into 2 of the most popular safety/reporting apps, WatchMe911 and Noonlight:

- These apps are only for 911, and do not include non-emergency (e.g., harassment) or transit-system-specific options,

→ so CTA riders’ only mobile option for help is to contact the police. - Moreover, neither app can detect elevation, which is particularly important for Chicagoans, as the CTA system includes buses and subway, ground-level, + elevated trains.

→ But there is also a clear need from users like Mayra who would benefit significantly from such an option.

Insights

From synthesizing both our interview and survey data, we noticed the same patterns and trends emerging and coinciding in both datasets- particularly,

- Riders feel particularly unsafe when they perceive themselves to be alone (especially at night).

- Riders are mainly worried about altercations with others (non-emergency situations that could develop into emergencies).

- Riders feel most comfortable when there is a visible CTA staff/security presence on trains, buses, and platforms; however,

- Many CTA riders do not always feel comfortable contacting the police- particularly if they perceive the event as a non-emergency.

Solution

Design Principles

Once we had a better grasp on both our users’ needs and the apparent gaps in solutions currently available for them, we crafted the following design principles:

Solutions should…

- Design a way for CTA riders feel less alone & more visibly connected to help (particularly at nighttime)

- Clearly communicate a system of action for help in the event of an emergency or adverse situation

- That provides riders with options of which system of action to take (911/Police vs. CTA Security/Staff)

- And provides feedback/acknowledgement of riders’ reports

- [And, ideally,] To prevent future crimes on the CTA [Either directly or indirectly]

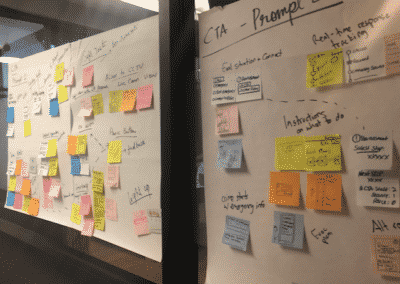

Ideation, Sketching, & Iteration

After completing a design studio in which we rapidly ideated solutions, we mapped our ideas and categorized them into concepts to identify common patterns. Of these, 6 main concepts emerged. We then sketched each concept out and evaluated:

- How well each addressed our design principles

- How each seemed to balance business needs (increased ridership) with user needs (feeling safe, connected to help, and informed).

We decided to hone in on two main features we believed addressed our design principles most effectively:

- Implement mobile call button options for reporting crime on the CTA

- With real-time feedback from CTA staff/authorities

- + instructions on what to do next

- Create a way for riders to track and share their ride with others

- With safety information of upcoming stops (staffing/security, etc.)

- Also allowing for faster, more effective reporting

Copyright © 2022 Sarah Alberti